Profile/Introduction

The late afternoon sun reflected off the edge of the high, sandy terrace, extending abruptly from the northeast highland, and everyone altered their course without a word, looking forward to a night on dryer land away from the river. It had been a long day, working down along the irregular lake shore, and then up the river past the falls and narrow gorges, searching without success for any of the small family groups of caribou still moving north to high elevations. Even when bundles were dropped, and nighttime preparations began near the foot of the terrace, the little ones moved quickly to edges above the river, crouching in the low sunlight behind willows and small clumps of bushes, still looking for movement in the floodplain. Although there was always food to share, roast caribou would be much more satisfying than the small pieces of rabbit and fish that had become their usual fare. As the sun went down, the watchers returned to the camp, now taking shape near the west terrace edge. Tomorrow was another day.

The late afternoon sun reflected off the edge of the high, sandy terrace, extending abruptly from the northeast highland, and everyone altered their course without a word, looking forward to a night on dryer land away from the river. It had been a long day, working down along the irregular lake shore, and then up the river past the falls and narrow gorges, searching without success for any of the small family groups of caribou still moving north to high elevations. Even when bundles were dropped, and nighttime preparations began near the foot of the terrace, the little ones moved quickly to edges above the river, crouching in the low sunlight behind willows and small clumps of bushes, still looking for movement in the floodplain. Although there was always food to share, roast caribou would be much more satisfying than the small pieces of rabbit and fish that had become their usual fare. As the sun went down, the watchers returned to the camp, now taking shape near the west terrace edge. Tomorrow was another day.

So it may have been some 12,000 years ago, when a small group of the First Vermonters moved up the river we now call the Winooski. There is evidence that a second visit by people following the same lifeway, a seasonal round covering hundreds of miles of territory, occurred about 1,000 years later. As the tundra environment changed and the river valley became more forested, other groups of people came up to the high terrace to enjoy the vantage above the river and the sunlight that streamed through the trees from dawn to dusk. A flurry of activity occurred about 5,000 years after the first visitors came and went but this time was more focused on the terrace edge closest to the river. As the tree cover grew and changed with the climate, most people living along the valley stayed down within the floodplain, and left fewer traces on the terrace above.

The trees were still thick when Europeans first moved into the Champlain Valley, and settlers began to develop the abundant falls above and below the gorges. Land clearing for agriculture soon followed and both the bottom lands and uplands, including the high sandy terrace were cleared of trees. Once again the sun shone un-impeded from morning to night across the forgotten campgrounds of the original inhabitants.

The Challenge

As Vermont addresses climate change concerns by encouraging the development of renewable energy projects, the most common type of project is the installation of solar farms. Vermont’s largely un-developed landscape is conducive for this type of installation. However, the intersection of sunny locations now, with areas used by Native inhabitants in the past for exactly the same reason to enhance their own lives, is setting up potential conflict. Since energy projects are regulated by the Vermont Public Service Board, historic site review, including archaeological sites, is a component of the review. The sandy terrace described above is now part of a one of the few remaining family farms in Chittenden County. Faced with increasing energy costs, the fifth generation farmers have embraced a new technology and are currently developing a 2.0 MW solar farm on the terrace, utilizing the same solar energy that attracted people to this location in the first place 12,000 years ago.

As Vermont addresses climate change concerns by encouraging the development of renewable energy projects, the most common type of project is the installation of solar farms. Vermont’s largely un-developed landscape is conducive for this type of installation. However, the intersection of sunny locations now, with areas used by Native inhabitants in the past for exactly the same reason to enhance their own lives, is setting up potential conflict. Since energy projects are regulated by the Vermont Public Service Board, historic site review, including archaeological sites, is a component of the review. The sandy terrace described above is now part of a one of the few remaining family farms in Chittenden County. Faced with increasing energy costs, the fifth generation farmers have embraced a new technology and are currently developing a 2.0 MW solar farm on the terrace, utilizing the same solar energy that attracted people to this location in the first place 12,000 years ago.

The Solution

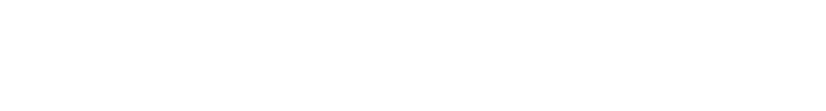

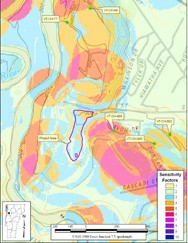

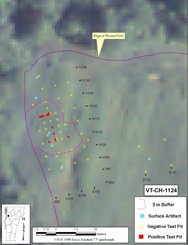

In this case, early consultation with the Division for Historic Preservation prevented potential project delays by identifying the steps necessary to complete cultural resource investigations well before the regulatory review at the Public Service Board was initiated. The geographical orientation of the high, sandy terrace above the Winooski River, along with other environmental variables that make up Vermont’s Environmental Predictive Model for Locating Precontact Archaeological Sites, indicated that overall terrace was archaeologically sensitive. The next step was to recommend that a Phase I site identification survey be undertaken in the project area prior to the construction of the solar farm.

In this case, early consultation with the Division for Historic Preservation prevented potential project delays by identifying the steps necessary to complete cultural resource investigations well before the regulatory review at the Public Service Board was initiated. The geographical orientation of the high, sandy terrace above the Winooski River, along with other environmental variables that make up Vermont’s Environmental Predictive Model for Locating Precontact Archaeological Sites, indicated that overall terrace was archaeologically sensitive. The next step was to recommend that a Phase I site identification survey be undertaken in the project area prior to the construction of the solar farm.